1. Analysis#

An Algorithm essentially is a sequence of instructions that maps input(s) to output(s).

Algorithms are the one of the oldest and fundamental concepts in computer science. They have endured over the years and are still extremely relevant because they can be designed, studied, and analyzed in a way that is independent of any programming-language and machine hardware.

This allows algorithms to be relevant indepedent of rise and fall in popularity of different programming languages as well as all the innovations and progress in computer processors.

This means that we need techniques that enable us to compare the efficiency of algorithms without implementing and executing them.

The three important abstractions that allow us to do so are:

Pseudocode - enables independence from any programming language

Random Access Machine - enables independence from any particular machine hardware

Asymptotic Analysis - enables independence from any particular input data

1.1. Pseudocode#

Pseudocode is a halfway point between human language and programming language, which allows us to focus on the algorithmic ideas rather than on implementation details.

Fig. 1.1 Pseudocode lies between natural language and formal language, on the axes of precision and ease-of-comprehension.#

By emphasizing ideas rather than implementation details, pseudocode is able to describe algorithms without being too formal, ignoring many of the tedious details that are required in a specific programming language. At the same time, pseudocode is more precise and less ambiguous than natural human language.

Consider the following pseudocode for an algorithm called DISTANCE, whose input is four numbers (x1, y1, x2, y2) and whose output is one number d.

DISTANCE(\(x_1, y_1, x_2, y_2\))

\(d \leftarrow (x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2\)

\(d \leftarrow \sqrt{d}\)

return \(d\)

Pseudocode is not a programming language. It is a simple way of writing programming code in English. It is used to design while taking into account the algorithmic paradigms.

Pseudocode is sometimes used as a detailed step in the process of developing a program. It allows designers or lead programmers to express the design in great detail and provides programmers a detailed template for the next step of writing code in a specific programming language.

Pseudocode generally does not actually obey the syntax rules of any particular language; there is no systematic standard form. For example, the following pseudcode is more formal than the previous pseudocode:

Algorithm 1.1 (Ford–Fulkerson)

Inputs Given a Network \(G=(V,E)\) with flow capacity \(c\), a source node \(s\), and a sink node \(t\)

Output Compute a flow \(f\) from \(s\) to \(t\) of maximum value

\(f(u, v) \leftarrow 0\) for all edges \((u,v)\)

While there is a path \(p\) from \(s\) to \(t\) in \(G_{f}\) such that \(c_{f}(u,v)>0\) for all edges \((u,v) \in p\):

Find \(c_{f}(p)= \min \{c_{f}(u,v):(u,v)\in p\}\)

For each edge \((u,v) \in p\)

\(f(u,v) \leftarrow f(u,v) + c_{f}(p)\) (Send flow along the path)

\(f(u,v) \leftarrow f(u,v) - c_{f}(p)\) (The flow might be “returned” later)

Some writers borrow style and syntax from control structures from some conventional programming language. Variable declarations are typically omitted. Function calls and blocks of code, such as code contained within a loop, are often replaced by a one-line natural language sentence. The common operators and their symbols in pseudocode are given below:

Type of operation |

Symbol |

Example |

|---|---|---|

Assignment |

← or := |

c ← 2πr, c := 2πr |

Comparison |

=, ≠, <, >, ≤, ≥ |

|

Arithmetic |

+, −, ×, /, mod |

|

Floor/ceiling |

⌊, ⌋, ⌈, ⌉ |

a ← ⌊b⌋ + ⌈c⌉ |

Logical |

and, or |

|

Sums, products |

Σ Π |

h ← Σa∈A 1/a |

Subscripts |

[] |

a[1] ← 0 |

Pseudocode is commonly used in textbooks and scientific publications that are documenting various algorithms, and also in planning of computer program development.

1.2. Random Access Machine#

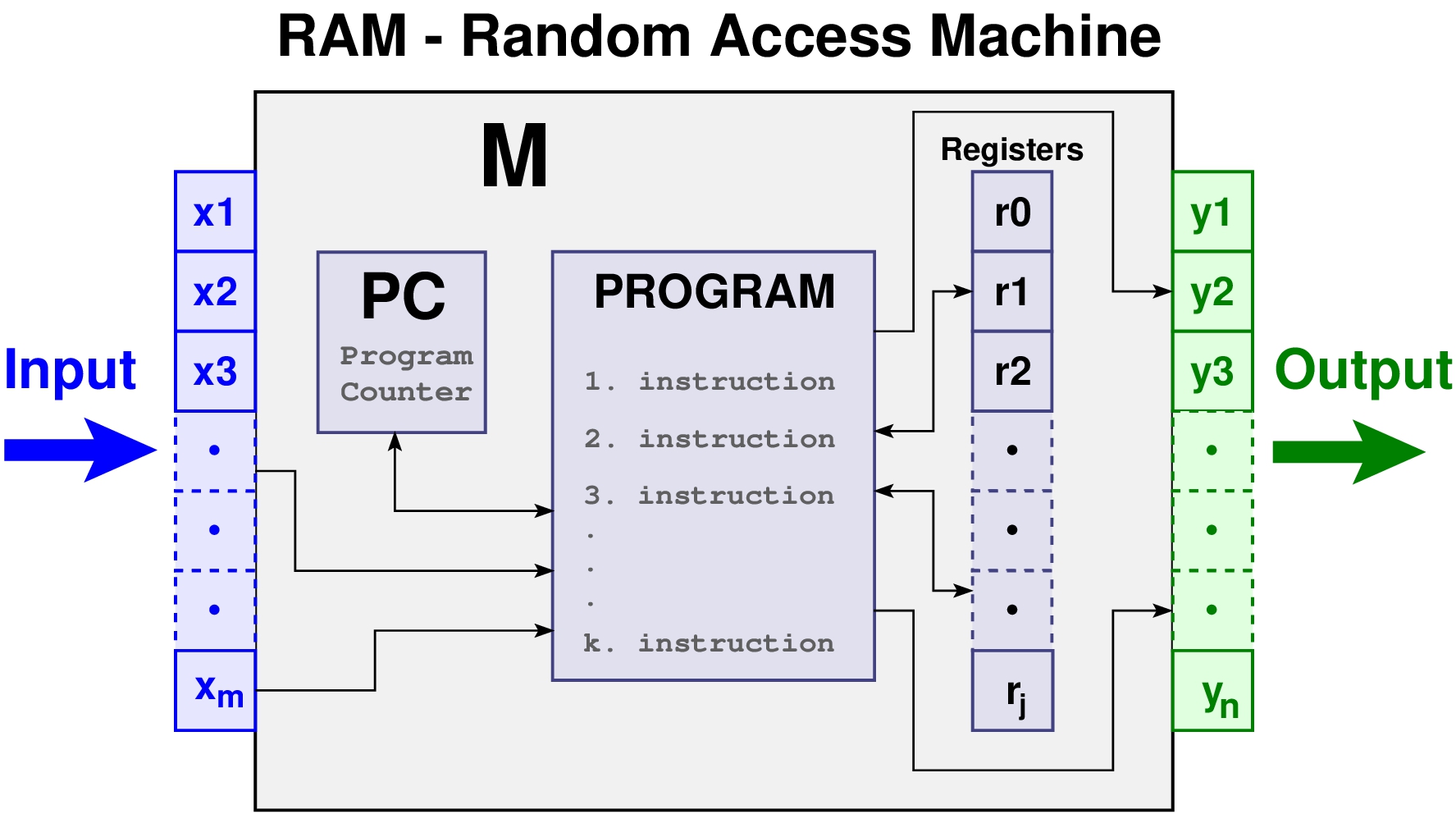

Machine-independent algorithm design depends upon a hypothetical computer called the Random Access Machine or RAM.

Under the RAM model of computation, we are confronted with a computer where:

Each simple operation (+, -, *, /, if, call, return, etc.) takes exactly one time step.

Loops and subroutines (aka functions, methods, procedures etc.) are NOT considered simple operations. Instead, they are the composition of many single-step operations. It makes no sense for sort to be a single-step operation, since sorting 1,000,000 items will certainly take much longer than sorting 10 items. The time it takes to run through a loop or execute a subprogram depends upon the number of loop iterations or the specific nature of the subprogram.

Each memory access takes exactly one time step. Further, we have as much memory as we need. The RAM model takes no notice of whether an item is in cache or on the disk. It also ignores the fact that memory access time is not uniform. In the RAM model, we can access any memory location in the same amount of time.

Under the RAM model, we measure run time by counting up the number of steps an algorithm takes on a given problem instance. If we assume that our RAM executes a given number of steps per second, this operation count converts naturally to the actual running time.

Fig. 1.2 Random Access Machine (RAM) is a hypothetical computer model that abstracts away unnecessary details. with an unlimited number of registers and a simple instruction set. The RAM model is used in algorithm analysis because it is simple to implement and it is not tied to any particular hardware design. You don’t need to worry about the specifics, just remember the three assumptions.#

The RAM is a simple model of how computers perform. Perhaps it sounds too simple. After all, multiplying two numbers takes more time than adding two num- bers on most processors, which violates the first assumption of the model. Fancy compiler loop unrolling and hyperthreading may well violate the second assumption. And certainly memory access times differ greatly depending on whether data sits in cache or on the disk. This makes us zero for three on the truth of our basic assumptions.

And yet, despite these complaints, the RAM proves an excellent model for understanding how an algorithm will perform on a real computer. It strikes a fine balance by capturing the essential behavior of computers while being simple to work with. We use the RAM model because it is useful in practice.

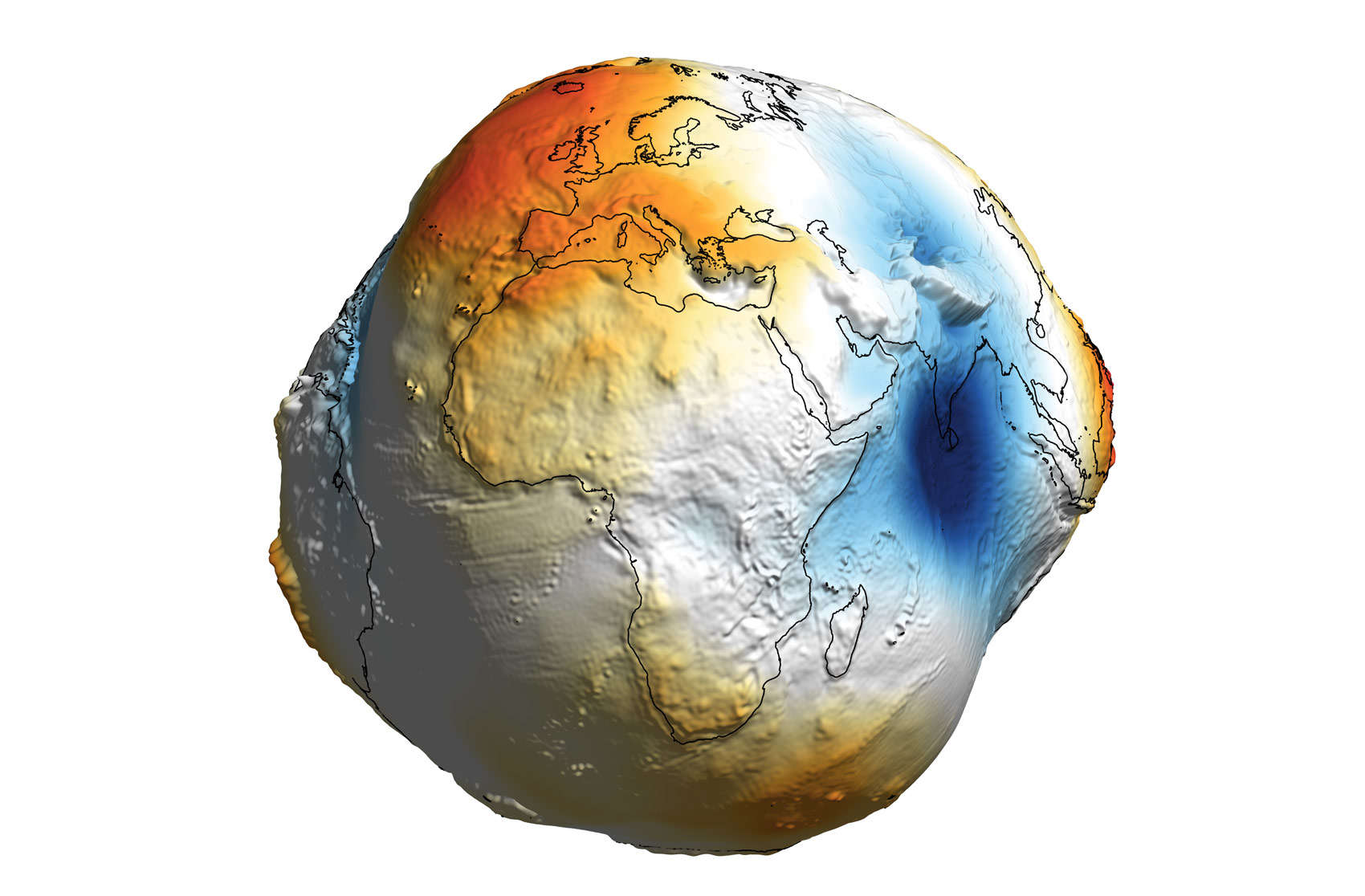

Every model has a size range over which it is useful. Take, for example, the model that the Earth is a sphere (or even an eliptical). You might argue that this is a bad model, since it has been fairly well established that the Earth is in fact technically a geoid. But, for most purposes, the Earth is sufficiently spherical that you can use the spherical model without getting into trouble. If you are trying to land a satellite on the moon, you might need to take the geoid into account. But if you are trying to drive to the grocery store, the spherical model is good enough.

Fig. 1.3 The Earth is not a perfect sphere. It is a geoid. But for most purposes, the spherical model is good enough. The same situation is true with the RAM model of computation.#

The same situation is true with the RAM model of computation. We make an abstraction that is generally very useful. It is quite difficult to design an algorithm such that the RAM model gives you substantially misleading results. The robustness of the RAM enables us to analyze algorithms in a machine-independent way.

1.3. Asymptotic Analysis#

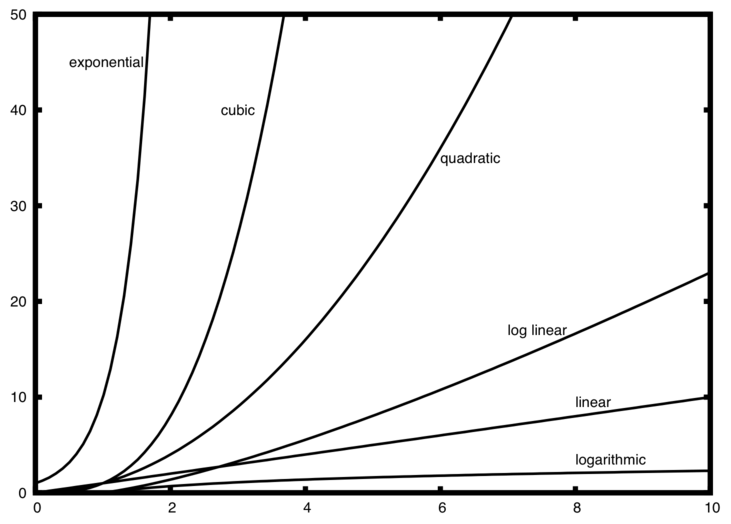

Asymptotic analysis is a method of describing limiting behavior.

Fig. 1.4 Comparison of growth rate functions.#

For example, the function \(f(n) = 3n^2 + 5n + 7\) is asymptotically equivalent to \(g(n) = n^2\). This is because the term \(5n + 7\) becomes insignificant as \(n\) becomes infinitely large \(n \rightarrow \infty\)”.

In other words, the term \(n^2\) ‘dominates’ the behavior of the function.

This is often written symbolically as \(f (n) \sim n^2\), which is read as “\(f(n)\) is asymptotic to \(n^2\)”.

Alternatively, if \(g(n) = n^2\) and \(f(n) = 3n^2 + 5n + 7\), we can write \(f(n) \sim g(n)\).

Formally, given functions f (x) and g(x), we define a binary relation

\(f(x) \sim g(x)\) as \(x \rightarrow \infty\), if and only if

\( \lim_{x \rightarrow \infty} \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} = 1\)

We say that a faster-growing function dominates a slower-growing one. When \(f\) and \(g\) belong to different classes and \(g\) dominates \(f\), it is sometimes written as \(g ≫ f\).

We say that \(f(n)\) and \(g(n)\) have the same asymptotic behavior, and write \(f(n) = Θ(g(n))\).